Wealth players tune into big brand beat

With banks looking to deal with fewer providers and clients finding comfort in brand names, the biggest fund houses are on the up

Banks are cutting down numbers of fund managers they are partnering with as big brands come increasingly into the ascendancy.

The process works both ways. Promoters such as Schroders, which tried to get their funds on as many global platforms as possible during the late 1990s, are now using resources to establish deeper relationships with fewer leading cross-border banks.

Swiss bank Julius Baer is “dealing with less houses” as clients rely on the bank’s “intellectual capital” to narrow down product choices for them, “monitoring performance on a consistent and ongoing basis.”

Leading private banking franchises are embarking on a conscious cull of products, in the interest of efficiency and to cut down costly and unnecessary discussion time between relationship managers and clients.

“We should be and are very comfortable with anything we put on our platform and sell to our clients,” confirms Mark Mason, global CEO of Citi Private Bank.

“We can still get the products you want if you disagree with our view of the world. But the quality of products representing our view has to have gone through robust due diligence.”

This is confirmation that the bold mass market initiative by German banks dating back more than 10 years is now catching on even higher up the scale and among global wealth players.

It is easy to forget how much of a shock the industry felt when Deutsche Bank, back in 2003, followed its smaller rival Commerzbank in a rush for top-brand agreements with a handful of external managers.

Back then Rainer Neske, head of Deutsche’s powerful branch network, signed agreements with eight partners including Fidelity, Franklin Templeton and Schroders to provide “top picks” of funds to be marketed to clients.

This system caught on across Europe and led to much greater investment by fund managers in their brands as they jostled for position on a consolidating number of wealth platforms.

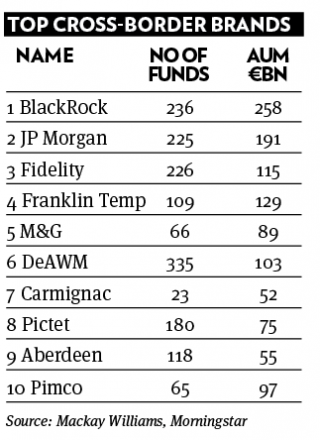

According to research on European fund brands from consultancy Mackay Williams in association with Morningstar, product complexity and volatile markets have increased customer reliance on comfort provided by brands. The biggest concern among banks selecting funds is the expected pan-European fee ban.

“This is driving demand for greater investment in brand spend and marketing materials suitable for the end in investor,” reads the introduction to the consultancy’s Fund Brand 50 report for 2014.

BlackRock has further cemented its place as king of the brands, with both Aberdeen and M&G rising fast, while Schroders has dipped out of the top 10.

Although one or two boutique managers are making their way up the charts, there is a massive challenge for smaller shops to penetrate wealth platforms.

The banks’ workload has increased dramatically as they are expected to research fund houses’ operational techniques and stability, in addition to investment performance and marketing resources. “Logically, they need to manage less relationships to a higher standard,” confirms Andy Sowerby, distribution boss at boutique house Martin Currie.

Fund houses say it is much tougher to get onto and stay on lists of recommended providers. As sales of funds become increasingly mechanised and relationship managers concentrate on market advice and asset allocation rather than product sales, the obsession with brands is likely to be fuelled further still.