Emerging markets well placed to weather storm

Kim Catechis, Martin Currie

Emerging markets remain better placed to succeed in today’s volatile global economy, though they would benefit from a return to growth in the West

When Martin Currie’s Kim Catechis moved his focus from European to emerging market equities in 1996, Portugal and Greece were still classified as the latter.

It is a sign of the times that these two countries are now in danger of returning to their former status, while the rest of the global economy looks on nervously, though the Edinburgh-based firm’s head of global emerging markets also tries to look on the bright side.

“This may be an incredibly stressful time, but it is also an exciting time without a precedent,” says Mr Catechis. “The issues facing the eurozone are an economic problem, but have become politcised, making a purely economic solution impossible.”

European governments are not clubbing together to sort the mess out, he laments, and are failing to sell the difficult decisions to their electorates. “This is a new world of me first,” he explains.

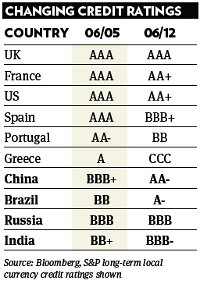

To make headway in such a volatile economic environment, a country requires three things, says Mr Catechis: a strong balance sheet, good technocrats and political will. Most of the developed world falls down on the first point, he says, and emerging markets are clearly better placed.

“China, Russia and Brazil would top the list, then India and South Africa, though their balance sheets are not quite so strong,” he explains.

Although emerging markets may be better placed than most European economies, they would clearly benefit from a more buoyant Western consumer to boost their exports, says Mr Catechis.

But this is not the only potential cloud on the horizon. Mr Catechis is concerned by the political situation in China, which he says is undergoing the least smooth transition of leadership for 20 years. In addition he highlights the debt built up in the country by state owned entities in the 1970s which is still there and keeps getting rolled over.

Martin Currie, which invests in international equites and has £5bn (€6.2bn) under management, and £158m in dedicated global emerging markets accounts, is all about fundamental, bottom-up investing and not macro-economics, explains Mr Catechis. They look for mispriced stocks following intensive due diligence, and plan on a five year time horizon, aiming for 45 stocks in the portfolio, making it fairly concentrated.

“Over the short-term, bottom-up investing can be frustrating,” he admits. “The obsession with macro economics makes it hard, as does the prevalence of passive investing such as exchange traded funds (ETFs). BlackRock and Vanguard are the biggest emerging market ETFs, and they affect all of us. There is a sense of rising and falling with the tide.”

He explains that as a stockpicker you have to make it very clear to clients on what you are trying to do. “Over the short-term we can get buffeted about and might not look very clever. It is essential that clients know what we are about and understand the time horizons,” adds Mr Catechis.