True diversity and inclusion all about culture, not quotas

Carol Geremia, MFS Investment Management

Leaders across financial services firms are determined to build more diverse workplaces although many are frustrated by the progress

Financial services firms claim to have made significant efforts in recent years to increase the proportion of minority groups within their workforce, fuelled by greater awareness of diversity benefits, social pressure and regulation.

While some have struggled with this effort to increase numbers, an even greater challenge has been developing a culture of inclusion, supported by leadership and educational frameworks, to ensure each employee, regardless of gender, race, age, sexual orientation, disability or social background feels valued and respected. Only by creating this sense of belonging and purpose can individuals develop their full potential and thrive.

These are among the key findings emerging from PWM’s Leadership, Diversity and Training survey, carried out in partnership with New York-based consulting firm Global Leader Group.

The study, conducted in March, canvassed views of 62 leaders. Geographically spread, with even male/female contingents, its respondents included CEOs and presidents, partners and founders, and regional and division heads, across a wide range of firms. These ranged from global private banks and asset managers to boutique wealth firms, family offices and fintechs.

The most striking outcome is that almost all leaders (98 per cent) are committed to fostering a diverse and inclusive culture within the firm. Eighty-six per cent are convinced that diversity can boost the firm’s performance and client acquisition metrics (see Figure 1), as different perspectives lead to a more robust decision-making process, and a workforce of individuals with different traits and characteristics helps firms better meet the needs of their diverse customer base. Broadening the talent pool also means hiring the best people, driving innovation and international reach.

“There is a widespread awareness of the fact that diversity and inclusion contributes to companies’ financial performance,” says Luigi Pigorini, head of Citi Private Bank, Emea. “While in the short term, homogenous teams produce better results, in the long term, diverse teams massively outperform homogenous ones. This is why it is crucial to invest in diversity.”

However, putting such knowledge into action proves more difficult, which helps explain why almost a third of leaders are not satisfied with the results achieved by diversity and inclusion strategies at their firm (Figure 2).

“You can certainly build a workforce that meets diversity quotas. But to allow that diverse workforce to reach its full potential, you need the mindset. And that’s culture, a shared belief system and common purpose,” states Carol Geremia, president and head of global distribution at US-based MFS Investment Management.

Her belief is that people unite around a common value, driving engagement and helping attract and retain a diverse workforce, while her main concern is of corporates’ “knee-jerk responses” around reaching diversity objectives. She divides diversity into two types: ‘low value’, uniting employees around a common purpose and ‘high cognitive’, allowing ethnically and socially diverse talent to bring different viewpoints, experiences and education to a firm. Successful enterprises need to combine the two.

“A culture where high cognitive diversity is appreciated and low value diversity is engrained not only meets employees’ deficiency needs, such as safety, trust and comfort, but also creates opportunity for deeper levels of motivation,” says Ms Geremia. Only then will employees aspire to meet their growth needs, such as purpose and service, improving job satisfaction and ultimately leading to better results.

Financial services leaders need to keep a long-term eye on employees, just as they do on investments, equating the level of responsibility in people’s careers to the value of their portfolios, generating trust, loyalty and commitment.

A company’s success should be measured by its ability to offer bespoke tools to employees who may be diverse by gender, race, sexual orientation, different background and experiences. These tools enable them to be successful, reach their objectives inside the firm and build their career within the industry, believes Craig Smith, founding partner and president of US investment and wealth firm Tiedemann Advisors.

Bigger pie

While the ability to attract, retain and promote diverse talent are key factors to meet diversity goals (Figure 5), implementing the right procedures to achieve greater inclusion is never plain sailing.

Promoting equity and inclusion can be “very painful”, especially for small to medium-sized firms, where hiring the highest-profile professional in a specific area might seem the easiest move. “Being committed to D&I [diversity and inclusion] involves a lot of discipline and willingness to have difficult conversations internally and creates a healthy friction,” says Mr Smith, who chairs his firm’s D&I committee.

One major misconception around diversity is that by broadening opportunity, someone else must lose out, but the reality is that “the pie just gets bigger” and everyone can be successful, adds Mr Smith.

This view is shared by other leaders. There is a misplaced concern that promoting diversity may put off successful high achievers who do not fit diversity/inclusion metrics, says Charlotte Ransom, CEO of Netwealth in London. Believing the diversity issue will somehow “resolve itself” is another major problem, while there is a “clear under-appreciation” of commercial benefits, she adds.

Diversity should not be treated as a “win or lose game”, states Eva Lindholm, CEO of UBS Wealth Management for the UK and Jersey. It is also wrong to believe that “clients care about commercial returns, and do not care how we get there”. This is confirmed by the phenomenal increase of sustainable and social impact investing solutions, aligned with investors’ values, without sacrificing financial returns.

While some respondents believe achieving a balanced and diverse workforce should be treated as an urgent issue, others are more pragmatic. “Low workforce turnover makes it a slow process, so setting unrealistic short-term targets is unhelpful,” believes Stephanie Butcher, CIO at Invesco. “Moreover, while data only really picks up gender, other ‘soft’ factors, which aren’t data based – such as how does it ‘feel’ to be a woman or a minority in the workforce – are also important,” adds Ms Butcher.

Other leaders stress that diversity criteria should not be met at the expense of meritocracy.

“Diversity and inclusion are very important but complex issues to solve and addressing them may lead to distortions,” says António Luna Vaz, general director of private banking at BPI in Lisbon. “The pressure to solve these issues quickly is so high that we may find ourselves disregarding meritocracy in order to fulfil diversity criteria.”

This mindset explains why diversity quotas are not believed to be effective by industry players. Only a quarter of respondents agree that quotas successfully promote diversity and inclusion (Figure 1).

Leaders have a responsibility to ensure diversity, because multiplicity of perspectives leads to best outcomes, points out James Bevan, CIO at CCLA Investment Management in London. Yet, even though professional headhunters are thoroughly briefed around diversity “the overwhelming majority of genuinely top candidates that come forward is still very male heavy and very white heavy,” he reports. “It will take time for that to change, and for diversity to build through to senior management, and it would be an error to compromise on the selection of quality in order to force more diversity,” adds Mr Bevan.

The effect of this pressure may be tokenism, still “very evident” in some companies, when a board populated by very similar people in terms of experience and background introduces somebody from a minority group, just to tick a box.

Another major preconception is that there is a lack of diverse talent. To combat this, leaders point to the importance of being creative, by engaging with different communities, with more diverse educational institutions and developing partnerships with minority-led financial firms.

The “persistence of unconscious bias, tendency to prefer ‘lookalikes’ and recruitment through conventional or traditional channels” is roundly condemned by Anne Pointet, deputy CEO at BNP Paribas Wealth Management.

“Diversity should be more about casting a wider net and getting the best team,” adds Marie Dzanis, head of Emea asset management at Northern Trust Asset Management.

Measuring diversity in the workforce, increasing transparency around pay gaps and linking salaries of executives to long-term diversity targets are believed to be key measures to boost diversity (Figure 5).

When it comes to pursuing gender equality in the fast-paced wealth management environment, the biggest issue is to find women to replace female colleagues who leave the firm, explains Citi’s Mr Pigorini. This leads to a “constant depletion” of female professional ranks, especially at the highest levels. It is crucial, therefore, to have a “very robust” succession and talent management process and identify sponsorship needs for promotion candidates. A pipeline analysis is also key. This allows leaders to work out the number of women they need at each level, to reach their diversity targets for top positions in the longer time horizon.

Debunking the industry myth that people are most productive in the 35 to 45 age bracket, Citi has introduced a ‘women returners programme’, aimed at supporting the return to work of female professionals after a career break. The project has resulted in “some very good senior older women” joining the bank.

Most leaders agree that diversity is not just about gender, although it is the easiest factor to measure. Almost 90 per cent believe the concept is extended to race, age, physical and mental abilities, sexual orientation and diversity of socioeconomic background.

Around 60 per cent have strengthened their commitment to racial equity over the past year, with the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on ethnic minorities and BlackLivesMatter protests further raising awareness. Yet, only 23 per cent are currently addressing the racial pay gap (Figure 5).

Broadening the talent pool to include ethnic minorities remains a challenge in wealth management, as there is much more awareness among white, privileged young people about wealth management firms and the financial world than there is in ethnic minorities. “We need to persuade black school and university leavers to consider wealth management as a career, and we need to show them how they can be supported in a career they may not previously have considered,” believes Michael Morley, CEO Deutsche Bank Wealth Management UK.

The lack of role models needs to be addressed too. “Ethnically diverse colleagues can lack role models in the organisation, which can increase attrition of this group,” points out Jean-Christophe Gerard, CEO Private Bank, Barclays.

More broadly, there is a lack of diversity of background in people entering the sector, who tend to be mainly university educated, from privileged backgrounds, says Mr Gerard, who believes “it is also important to broaden the diversity agenda beyond gender and ethnicity, to encompass all diversity types”.

Diversity of education

Another industry misconception is that the best people in the financial services sector come from top universities and studied finance, states Ali Jamal, founder and CEO of wealth manager Azura in Monaco. “We believe talent can be found everywhere in this world, across institutions and across industries,” explaining that a South African engineering graduate together with a former officer from the Royal Navy can think of “new client solutions from different vantage points”.

The desire and need to broaden the talent pool, and the search for strong leadership skills has driven banks such as Citi to focus on training individuals such as former military personnel, or former sports professionals, believed to have strong work ethics.

Addressing employees’ unconscious biases is a top objective of training sessions for almost 20 per cent of leaders, after enhancing ‘client first’ mentality, improving soft skills and digital capabilities (Figure 3).

“It is important to remind people that we do have unconscious biases, and it is important to mitigate them, especially during recruitment, during performance appraisal, and when assessing remuneration, to make sure the system is based on meritocracy and equity,” says Amy Cho, CEO, Hong Kong and head of intermediary, Asia-Pacific at Schroders.

Several leaders share the view that one way of dealing with unconscious biases, in addition to training, is ensuring that interview panels, both for entry level and senior level candidates, are diverse.

Mentoring in reverse

Leaders place great emphasis on mentorship and sponsorship, with 70 per cent of them believing it is the best way to attain trained and qualified staff (Figure 4).

While in the traditional form of mentorship, the person with greater experience, the mentor, advises the mentee, in Hong Kong, Schroders has implemented reverse mentoring, where millennials mentor non-millennials. Ms Cho herself joined the programme, “to learn more about the thinking of millennials and their needs,” and to make sure the company can support those needs.

This initiative is now evolving into a new ‘buddy programme’, based on the belief that two people of different ages and backgrounds can share work and life experience. Ms Cho actively encourages all line managers to take part in these initiatives, sponsored by the human resources department, but driven by employees’ groups, believing it is important for leaders to “walk the talk”.

A quarter of respondents agree that searching for excellent leaders who can bring teams with them is the most effective strategy to acquire talent. “One of the most difficult missions for a leader is to encourage and inspire others to follow,” says BPI’s Mr Luna. “If you can bring in a leader that has the power to bring the team with them, that should certainly be a good indicator”.

Building a diversity culture is a journey and takes time. One way to accelerate the process is to hire inclusive leaders, says Citi’s Mr Pigorini, noting those individuals, who at some stage of their career or life have not felt included, become much more inclusive leaders.

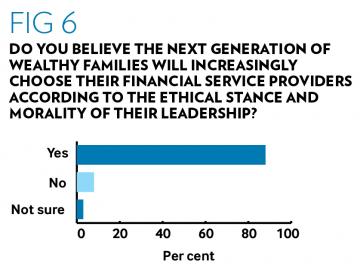

These individuals are crucial to meet the needs of the next generation of wealthy families, who increasingly choose their financial service providers according to their ethical stance and morality of their leadership, according to 88 per cent of survey respondents (Figure 6).

“If you populate your senior leadership team with people that are inclusive, eventually you do manage to change the culture, pretty easily,” concludes Mr Pigorini.