Bespoke mandates turn house views into reality

Respondents to PWM’s twelfth annual sub-advisory research survey believe increased regulation and the promise of enhanced returns mean the use of third party managers will continue to grow

The sub-advisory model is enjoying a renaissance, as wealth managers and private banks increasingly delegate the management of client assets to specialist investment firms. This is one of the main findings in PWM’s twelfth annual European sub-advisory survey, based on interviews with 30 asset managers and wealth managers, private and retail banks, as well as life insurance companies and fiduciary managers. Together, they manage €2,800bn in total assets, of which around 20 per cent (€553.8bn) is managed by third-party managers – 533 sub-advisers in total, an average of 28 each.

Around two thirds of respondents believe use of the sub-advisory model will grow in Europe over the next two years. Partly, this is a result of regulation such as the Retail Distribution Review (RDR) in the UK, and similar versions in Switzerland and the Netherlands, which have banned retrocessions, and the likelihood that MiFid II will prohibit kickbacks from 2017.

“The abolition of distribution fees in these regions is having a big effect on business,” says Martin Mlynar, head of Robeco’s Corestone multi-asset multi-manager in Zug, “and the same will surely happen in Italy and Spain as customers begin to understand how many basis points of their money is being used to satisfy distributors.”

However, several respondents also said that a major reason they use sub-advisory is so they can set up funds that are more effective in implementing their broad house view, especially when there may not be a clear way of doing it in the market. Investment returns can theoretically be enhanced by designing portfolios that fit well with the wealth manager or private bank’s view on asset allocations and risk, perhaps with more concentrated stock selection or a greater appetite for volatility than would be allowed in an off-the-shelf fund.

Top 5 drivers to sub-advise

• Search for higher alpha

• Funds specifically tailored to client’s needs

• Focus on core competency

• Competitive differentiator

• Reduced investment management risk

For many large players in wealth management, size is a big issue. “We are concerned about liquidity and the concentrations taken in funds due to our size,” says Gareth Thomas, portfolio manager at UBS Wealth Management UK, referring to the high yield space in particular.

“Using this sub-advisory model, we can apply our house view clearly and increase liquidity and capacity, which gives us access to managers we would not normally invest in, such as one that only runs US mutual funds but not European funds; and sometimes because they are too small or where the fund is closed. We try to get all our best ideas into a portfolio and that can be in less liquid parts of the market.”

William Pompa, senior vice president at fixed interest specialist Pimco, says the firm has at least five new clients who will be launching some novel funds by the end of the year, and that it has recently received enquiries from banks and wealth managers who have never used sub-advisory before. “The new demand is not for off-the-shelf funds; they want flexibility that meets the end clients’ exact needs that they cannot find in existing products,” he says.

“One aspect is funds with a focus on risk management and another would be funds with alternative flexible approaches. It is not enough to know exactly what is in a fund, you also need the ability to tailor the product.”

As the major bull runs of the last six years come to an end, firms are thinking about new investment styles that are less tied to the direction of the market such as liquid alternatives, absolute return funds, and flexible approaches to cash and cash equivalents.

The ever-changing regulatory backdrop is also a spur and firms take comfort from signing up with partners with broad capabilities, with whom they can talk through different approaches and stay on top of the constraints in different markets such as regulations, fee models, the type of investments allowed and limitations on leverage.

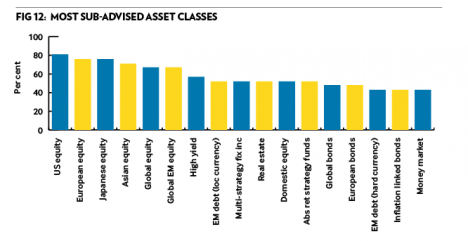

Consequently, a greater proportion of mandates are now bespoke, with 55 per cent of the respondents now saying that this applies to over 90 per cent of their mandates (see Fig 1). The preferred type of manager is still the specialist (for example managing regional equity/regional debt or niche asset classes), with 86 per cent saying they prefer specialist managers now, and 76 per cent saying they will continue to prefer specialists in the future.

Preference for global managers, typically managing global equity or global fixed income, has increased over last year, with a third of respondents now preferring global firms (see Fig 2), versus 11 per cent last year. The multi-boutique model has been gaining interest, with more respondents preferring multi-boutique asset managers this year (43 per cent) than did so in 2014 (11 per cent).

While many firms are using the sub-advisory model to push towards greater idiosyncrasy and sophistication, insurance companies typically stick to traditional vanilla asset classes, owing to their capital constraints.

“It is not as simple as the risk/return profile, or assessing the correlation or return benefit compared with other asset classes,” says Phil Clements, head of investment at LV. “With these non-traditional areas when we come to assess the stresses, and how much capital strain these vehicles require, then the argument usually ceases to add up.”

Around half agreed that the ban on inducements has led wealth managers and private banks to sub-advise more as opposed to buying off-the-shelf funds (48 per cent) and that regulations such as RDR in the UK or Mifid in Europe will drive these firms to sub-advise more in the future (52 per cent) (see Fig 3 and 4). More generally, more than 60 per cent expect sub-advised assets and number of mandates to grow over the next 12 months.

Top 10 selection criteria

• Long-term consistent fund performance

• Investment style (and consistency of invest style)

• Risk Management

• Track record

• Fee level

• Management team

• New fund with an interesting story

• Brand/Good reputation

• Fund Capacity

• Top quartile fund performance

As the sub-advisory model is not easy to establish and implement, the rewards for adopting it must be commensurate. “Sub-advisory comes with issues and costs related to negotiating the mandate, need for scale/ high minimum investment amounts, governance structure and risk controls, problem of pooling for different kind of investors, not necessarily at lower costs and for the fund managers themselves, segregated accounts might also be more expensive to manage,” explains Theo Nijssen, director Multi-Management at Kempen.

“One way for distributors like ABN Amro to get around the RDR in the Netherlands is to build or expand their own fund of mandates umbrella. I expect other big banks such as Rabo/ING in the Netherlands to follow.”

This year for the first time we asked respondents which of their team members is responsible for selecting sub-advisers and for monitoring them. This produced a varied set of responses (see Fig 5), but usually while individual senior staff may be involved in selecting sub-advisers, it is typically down to a team to subsequently monitor them. The most popular period for formally reviewing sub-advisers is once a year (55 per cent), followed by once a quarter (30 per cent) (see Fig6).

Fund performance and personnel changes are still the key reasons why a manager may be terminated, cited as a ‘top three’ reason by 93 per cent and 73 per cent of the respondents respectively, while style drift was the third ‘top three’ concern mentioned by 60 per cent of the sample (see table). Respondents said they switch managers as others may be a better fit with their strategies or have better risk/return characteristics. Sometimes they feel nervous that the asset manager’s fund is too big and reducing fees can also be an imperative.

None of our respondents replaced more than 30 per cent of their sub-advisers per year (see Fig 7). More than 50 per cent said they had replaced 10-20 per cent, while more than a quarter said 0-10 per cent, which in many cases meant they had yet to terminate any manager.

Sustainability has become more important in terms of ongoing relationships than a few years ago. “But client demand lags what the bank is doing in regard to sustainability,” says Karolina Hutter-Rehrl, senior manager, Fund Management, at Länsförsäkringar Fondförvaltning AB.

“We see it as our duty in the investment area and believe that clients will demand it in future. Clients are not very enlightened at the current time. The industry must take the lead in corporate governance.”

The most frequently used asset managers in our sample are BlackRock, Schroders, JP Morgan, Aberdeen AM and Franklin Templeton (see Fig 10). Invesco was rated very good by around one third of the respondents, while Aberdeen AM and BlackRock were each rated very good by around one quarter (see Fig 8).

Overall, the performance of the sub-advised funds has improved on last year. Over three quarters of respondents can claim some success with more than half of their funds outperforming their benchmark this year versus 62 per cent last year. Half reported that 50-70 per cent of their sub-advised assets outperformed their benchmark, and a further 27 per cent said that more than 70 per cent of their funds outperformed the benchmark (see Fig 9).

This level of performance is scarcely shooting the lights out, however. Partly that may be a result of the model’s historical weakness, as in plumping for ‘best of breed’ managers there has been a high degree of convergence in some strategies and sometimes a detrimental commonality of holdings. There is much more opportunity to add value through a mix of more concentrated portfolios, such as in a multi-asset/multi-manager approach. But more than 70 per cent of respondents still have the majority of their money in individual funds, compared with 27 per cent in multi-manager funds.

More generally, “investment managers seem to have phases of popularity – people go through disappointing periods and in and out of vogue – and there is only a very limited number of consistently performing managers and a degree of mean reversion,” says UBS’ Mr Thomas. “Take, for example, growth and value styles: we hold BlackRock US Basic Value which has underperformed the S&P500 because growth has been doing better, but it has done well compared with its benchmark.”

Over the years, performance measurement has become much more sophisticated, with greater importance attached to the evaluation of risk management and compliance, and a proliferation of specialist research firms assist our panel in monitoring their sub-advisers. Arguably, there are risks in so many fund distributors using similar inputs from the same or similar analytic firms, as this creates groupings around certain funds and strategies, particularly in the equity space.

“The key is in the implementation,” adds Corestone’s Mr Mlynar. “We are not claiming to find the best managers, but the most suitable in the process of portfolio construction. It is great to look at the strategic asset allocation, but the difficult part is not to lose that in the translation. Really getting the strategy implemented in the way we want is the challenge.”

Case Study: The traditional user

Wealth manager St James’s Place has used sub-advisers since it was founded in 1992. There has been a natural development as the fund offering has expanded into different geographies and sectors.

The firm will be launching a fixed income multi-strategy fund in future, as a complement to its existing range, reveals CIO Chris Ralph. “Currently our fixed income funds are long-biased so such a fund would provide a different source of returns,” he says. “It is hard to find a single manager who can do it all as they need to be multi-disciplinary so I think it is more likely to be a multimanager solution.“

UK equity income, US equities and global equities are some of the most difficult areas, where only a small number of managers outperform, says Mr Ralph. “Talent is not easy to come by in any market sector but in the larger and more popular sectors, it’s even more challenging. We try to identify that talent without bypassing our standards.”

The wealth manager has a low rate of manager turnover, a figure distorted when £4.5bn (€6.1bn) of client money followed Neil Woodford from Invesco to WMI in 2014. “A lot of the turnover is driven by manager departures and it is not inconceivable that some market environments will precipitate more departures than others,” adds Mr Ralph.

“Style drift is a good example of the importance of monitoring, as it is hard to predict when a manager may start being distracted,” he adds. “It may be that they are under pressure but this is not the only reason.” For example, he says, a manager who historically had a bias to mid-caps may drift into large caps because in this way the liquidity profile of the fund is maintained. And drifting into large caps will in turn attract more AUM because the manager can tell clients that they have a process that is as applicable to large caps as to mid caps.

The wealth manager has an extensive investment committee, with access to research firms such as Inalytics, which provides transition manager analysis, and Reddington whose core competence is in fixed income and alternatives and is advising on the revision of SJP’s multi asset fund.

“Risk management is more important owing to the fiduciary duty we have as a wealth manager,” says Mr Ralph. “The sub-advisory model demands scale as there can be difficulties in practice. Monitoring is more difficult, so the organisation needs depth to manage this well, and to be able to give the client less, rather than more, risk.”

Case study: The newcomer

Seven Investment Management (7IM) currently tends to invest in off-the-shelf funds, not segregated mandates, but the asset manager is in early discussions with investment firms about sub-advised arrangements.

There are already grey areas as some investment banks have created baskets for the firm, to give it certain exposures to reflect its house view and to sit well with its asset allocation strategy. For example, Bank of America Merrill Lynch has put together a basket of cash-rich Japanese stocks where the managers are looking to increase the return on equity.

In other areas, the firm is in discussions with managers to provide their best ideas, or the largest active weights in their portfolios. However, 7IM could conduct the trading itself, a novel arrangement.

“It is tremendously exciting, and could be the next evolution in a more tailored approach for our clients,” says Damian Barry, portfolio manager. “It’s all about amplifying the alpha, leaving us to worry in our asset allocation about the beta and volatility.”

Currently, most sub-advised funds are merely replicas of off-the-shelf funds, argues Mr Barry, and are sub-advised primarily to push down fees and increase control, rather than to intensify alpha-generation.

“It is difficult to find good funds that have been out of favour, such as value or cyclical funds,” he adds. “There is not a lot of product choice.”

Segregated accounts definitely have appeal but there are operational aspects such as the need to set up guidelines, the monitoring function and the middle office, and how to deal with voting issues and shareholder engagement. “Some managers may not be eager to do it unless it was for an account that could keep growing,” he says.