Seeking partners to help lift returns

PWM’s tenth annual sub-advisory research survey finds clients happy for private banks to outsource mandates to third parties, but relationships need to be nurtured

Private banks – despite much talk about service, branding and technology – are embarking on a relentless search for alpha, according to PWM’s latest research. They are also keen to enhance their menu of products offered to clients, while looking for a certain freedom to focus on their core competency.

These are the main three reasons why many major wealth managers are hiving off certain asset classes to be managed by external fund managers, on what is known as a ‘sub-advisory’ basis. There is no longer any shame not being able to do something yourself, runs the increasingly accepted wisdom, as long as you “know a man who can”.

But just knowing a specialist is seldom enough for demanding clients. To succeed, a bank needs to be prepared to go into a deep partnership with an external specialist. And it might take a couple of years for both partners to size each other up and negotiate each others’ strengths and weaknesses.

These trends are uncovered in PWM’s annual sub-advisory research survey, which marks its tenth anniversary in 2013. The survey is based on interviews with 40 private banks, wealth managers and asset managers, keen to share their business plans with us. Between them, they represent sub-advised mandates for nearly 640 different investment products.

Typically, an asset manager wanting to gain access to a specialist asset class, in which the institution does not have its own skill-set or track record, rather than going to the expense of building an in-house team and recruiting investment professionals from rival houses, finds the most cost-effective solution is often to outsource a sub-advisory mandate to external fund specialists.

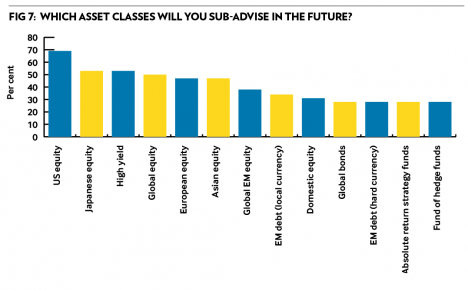

In 2013, one of the most popular asset classes, in terms of private client demand and recommendations from investment experts, has been Japanese equities. The advent of ‘Abenomics’ has spurred huge hopes for a reversal in fortunes of a stock sector apparently doomed since the late 1980s, still searching for a new dawn.

Investment houses have recently dipped a toe into these notoriously choppy waters for finding value-adding managers. Standard Life Investments (SLI) has partnered with Japanese house Chuo Mitsui Asset Trust and Pioneer Investments with Mitsubishi. Private banks are also expected to follow with sub-advisory arrangements, while some prefer to recommend third party funds to clients.

Prior to the 2008 crisis, hedge funds were flavour of the month, sparking a similar rush of interest from excited private clients. Essentially, wherever an asset class is geographically distant, culturally challenging or slightly opaque, the sub-advised virtues of greater transparency and operational comfort regarding the administration, custody and oversight of assets come into their own.

Regional arrangements can also open the door to a new marketplace. Under the terms of Standard Life Investment’s partnership, Chuo Mitsui will manage and sub-advise a $1bn (Ä750m) chunk of SLI’s Japanese equity fund and SLI will also sub-advise $1.2bn of Chuo Mitsui’s global equity funds.

“This is not about building something for one year or three years, the arrangement needs to be around for the long term,” says Vinnie O’Brien, head of strategic alliances at SLI. “We talked to Mitsu for two years and a big part of that process was making sure it was a like-minded organisation we wanted to partner with.”

High yield products are also currently under the spotlight. Frankfurt-based Union Investment, which generally uses a fund platform, has entered a sub-advised relationship with Munich-based boutique XAIA for its Credit Basis strategy based on leveraging discrepancies between bonds and default protection, which targets three month Euribor plus 3 to 3.5 per cent pa net of fees.

Italian asset manager Euromobiliare, which currently uses sub-advisers for fixed income, envisages setting up an arrangement for high yielding equities. Paolo Biamino, head of the group’s fund selection unit, notes that while demand is also strong for absolute return strategies, owing to their complexity the tendency is to put a few mutual funds into a diversified portfolio rather than committing to one single manager.

Top 10 selection criteria

• Long-term consistent performance

• Management team

• Investment style

• Top quartile fund performance

• Track record

• Risk management

• New fund with an interesting story

• Competitive advantage

• Exclusivity of fund distribution

• Fees

“In the current environment we see a growing interest for flexible products with real dynamic allocation to different asset classes and risk factors,” says Oreste Auleta, head of wrapping and product management at Italian fund house Eurizon Capital.

“Nowadays, clients are not just looking for exposure to further betas. In addition to the search for really specialised managers in new asset classes, the present challenge for the sub-advisory business is the search for funds with really flexible exposures, either through wrapping different strategies or by selecting a single manager.”

The fourth most cited reason for setting up a sub-advised fund is the ability to tailor the fund for the client, often by requiring a more concentrated portfolio with less “padding”.

“One of the main reasons to use a sub-advisory arrangement is to tailor a product for our client base,” says David McFadzean, managing director of investment solutions at Royal Bank of Canada. “It is not a strength for a wealth manager just to offer a particular fund, because clients can generally buy this themselves.”

RBC typically demands greater defensiveness from its sub-advisers, and sometimes stipulates that any stock which falls by 25 per cent over a three -month period should be automatically sold.

These trends for tailored solutions tie in with findings from a recent Cap Gemini survey showing high net worth clients increasingly prefer the simplicity of fewer financial relationships with providers.

For wealth managers, this trend points to investing in unconstrained, flexible, multi-asset mandates, particularly as the mantra of a rigid asset allocation based on the traditional risk/return behaviour of asset classes has begun to break down.

“I feel we will move towards an environment where individual benchmarks relevant to investors’ goals will become more prevalent,” says Andy Brown, investment director at M&G. “This will mean that any asset allocation process will need to reflect that. Having a composite benchmark may be less relevant than having one defined by the client’s growth, income or risk requirements.”

Currently our survey respondents, which together have outsourced more than Ä200bn to be managed by third-party managers on a sub-advisory basis, prefer to opt for a portfolio with a single manager, although there are also significant assets invested in multi-manager portfolios.

In practice, the majority of sub-advised mandates are awarded to the big-brand players – the likes of BlackRock, JP Morgan and Schroders – who go to great trouble to attract this type of business, and whose scale provides comfort, implying a certain level of resources behind the customer relationship set-up.

Good long-term performance and a strong management team head the survey respondents’ wish list when looking for a sub-adviser. But in reality, there are few blue chip organisations that can boast everything it takes to succeed: scale, depth in their teams, robust infrastructure, experience in running tailored mandates, a compatible business model and a sensible incentive structure – the latter being an area that is now probed intensely.

BlackRock and JP Morgan were the predominant sub-advisers cited by respondents, used by 40 per cent and 37 per cent of the sample respectively. They were also rated as some of the best, alongside Pimco, Investec and State Street.

A number of smaller shops are also winning some sub-advisory business – our survey named 140 asset managers used by private banks and other financial institutions, although many only run a handful of mandates.

Logically, the sub-adviser model should help to integrate small players, says John Ventre, head of multi-manager business at Old Mutual Global Investors. “One of the key reasons for choosing a sub-advisory structure is that it means you do not have to migrate to the biggest funds,” he says.

“The model delivers better access. Unless a fund is segregated, it is impossible to get a meaningful amount into a smaller fund and the bigger funds all hold the same thing. So a segregated account structure actually allows you to give more to smaller fund vehicles.”

He names for example, fixed interest asset-backed specialist TwentyFour AM and the Chicago-based growth boutique Cupps Capital Management, which each run around $1bn in assets, of which $150-200m and $80m respectively is sub-advised for OMGI.

But despite unlikely descriptions of “reciprocal win-win relationships”, there are many problems associated with this business segment. One criticism often levelled at sub-advisory relationships is that managers are difficult to remove, in comparison with funds on a platform which can be sold at will, and to an extent this is backed by our survey, where partnerships have not changed greatly year on year.

Another criticism is high, multi-layered fees where a lot depends on the economic backdrop as a high performance/fee equation works better in a bull market. This year it is noticeable that almost all the funds in our survey charge between 0.5-1.5 per cent. Higher fees are no longer acceptable, and any distributor with the Ä40m it takes to open a sub-advisory relationship according to the research, will be able to negotiate lower fees.

Charges remain a sticking point for many. David Bailin, global head of managed investments at Citi Private Bank in New York, says Citi uses sub-advised funds for five to 10 ‘very niche’ sectors such as energy and convertibles. The reason sub-advised products are so limited is that there are two layers of fees and “we want to give access to the manager for the lowest price”.

Citi’s segregated mandates are usually bespoke, potentially including prohibition of a certain credit risk or category of investment. “For example, we might want junk bonds, but not the ‘junkiest’ bonds,” says Mr Bailin.

Currently, sub-advisory arrangements are losing out to a major rival trend, that of guided architecture, where private banks guide their clients through a limited range of pre-selected funds on a platform, with proportionally greater vetting and analysis.

“Consolidating the number of providers means there are fewer to manage from the perspective of risk management, and a bigger incentive for the distributor to work with you, so better commercial terms and educational and marketing resources can be negotiated,” says Cedric Bucher, head of business development at Architas Multi Manager. He points out that flagship financial advisory firms such as Hargreaves Landsown have recently trimmed back their platforms to 50 funds.

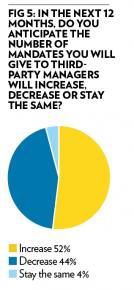

This is one of the reasons sub-advised assets have not grown by as much as might be expected. A slim majority (52 per cent) of respondents thought their sub-advised business would continue to grow. But looking across Europe, the sub-advisory market depends largely on the local regulatory landscape and business climate.

Markets such as France, Italy and Spain, where the top banks control captive distribution with proprietary products, offer few opportunities. Germany, on the other hand, is a distinct market with 422 savings banks that lack their own asset management capability.

Berenberg is the exclusive cooperation partner in sub-advising more than 100 of these banks. Peter Reichel, Berenberg’s deputy head of global investment strategy, says: “We started this business 12 years ago and it has grown rapidly because the savings banks needed proper investment funds and professional private asset management solutions, and additionally, using an outsourced service gives them an opportunity to cut costs in this field.”

The product ranges on offer by the savings banks are highly geared to the appetites of smaller investors, and must therefore be highly liquid and transparent. It is in these geographical, market and regulatory pockets of opportunity that the sub-advisory business is expected to grow, backed by some of the biggest global names in fund management.

See this year's roundtable discussion on the European sub-advisory landscape