Middle Eastern and European elites seek Jersey’s protection

James Mulholland, Carey Olsen

Jersey is becoming something of a centre for alternative investments while there are also signs of private banks returning to the island

Wealthy families are increasingly seeing Jersey as an efficient hub for managing and structuring assets. “Jersey has been pretty good in recent times at attracting family offices and ultra high net worth individuals,” says Nigel Cuming, chief investment officer at local wealth manager Cannacord Genuity.

Financial centres profiles

Law firms such as Bedell, work more and more with family offices. Holidays entrepreneur David Crossland, who set up the Airtours tour operating company and its in-house airline, International Airways, in 1990, is believed to be a client.

In addition to invoicing, financial reporting and tax, Bedell becomes involved in managing investments for such clients, also maintaining their aircraft, boats and overseeing philanthropic work, as well as offering guidance on passing wealth to the family’s next generation.

“We have seen an increase in this type of business fuelled by entrepreneurs who want to increase their investment levels,” says Bedell director Ian Slack. “There are not many people who can run a full-scale family office with a team of five in any other jurisdiction. Historically, this work was more tax-driven, but this resulted in skills and expertise being built up in Jersey, where tax is no longer a factor.”

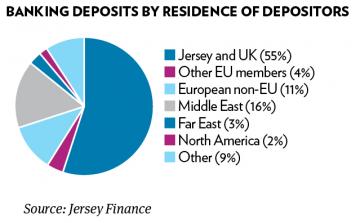

Clients from the Middle East are particularly attracted to these services, with Saudi Arabia accounting for 90 per cent of Gulf wealth, but business is also coming in from Bahrain, Doha and Dubai.

“They are concerned with security issues and the rule of law and see Jersey as a safe, well-regulated location to hold inter-generational assets for a nice nest-egg,” says Mr Slack, listing the Sunni-Shia conflict, the Yemen war, deteriorating relations with Iran, a falling oil price and scepticism about whether the House of Saud can maintain growth and stability as paramount in the minds of many clients. Typically, they first used Jersey structures to hold property purchased in London, before branching out into other services offered by island firms.

But things were not always so squeaky clean in these parts and Mr Slack acknowledges “it was a different world in the early 1990s, to what we see now,” with regular banning orders helping to police any transgressors out of the 12,000 strong financial services community.

The island’s government came to a crossroads in the 1990s, leading it to make a major decision about its direction. “We asked ourselves: will Jersey be a bottom feeder or a regulated financial centre in a meaningful way?” says Ed Shorrock, director of regulatory services at litigation and dispute resolution practice Baker & Partners, with the regulator opting for the heavy-handed, “shock and awe” approach of closing down uncompliant businesses.

“The regulator acted like my school PE teacher,” recalls Mr Shorrock. “He said, ‘I will be a complete nightmare to start with, and then become more relaxed.’ It was a good idea, as the early years were spent weeding out the real cowboys.”

While offshore financial centres, including Jersey, have been back in the news since the release of the Panama Papers earlier this year, failing to avoid tax evasion has been a criminal offence here since 1998 and a corporate registry showing who really owns locally incorporated companies has also been in existence since then. If the UK’s National Crimes Agency needs information aboutJersey-registered interests, it is provided within 24 hours, or one hour if a serious crime is involved.

“All of these things made us very different from the Panama problem,” says Geoff Cook, chief executive of industry promotional body Jersey Finance. “The challenge is to get that across to the UK public. We believe we are a clean jurisdiction,” having taken action against rogue businesses 30 years ago, after money was laundered on the island following the infamous Brinks Matt gold bullion robbery.

The occasional public shutdown still sends a chill wind through the industry and helps maintain standards, he says.

“That sort of news on a small island like Jersey gets around very fast and frightens the life out of people,” agrees Steve Meiklejohn, partner in the Trusts Advisory Group at Jersey law firm Ogier.

This community, concerned about keeping its livelihood, currently works so profitably that private equity firms, including Inflexion, are returning for regular bites of Jersey’s fiduciary companies, tempted by their thriving company and trust formations businesses.

The trust business offers “good multiples” with a “lot of private equity money looking for opportunities”, as banks de-risk and hive off non-core trust companies, says James Mulholland, a partner specialising in the funds business for law firm Carey Olsen.

Interest in this business has been boosted by more demand from European clients for structuring of trusts and companies, fuelled by European instability.

“The European client base is wider than several years ago,” says Mr Mieiklejohn. “There is an element of insecurity due to the euro crisis, which made people worried of being in certain countries. It’s not tax driven, it’s about stability and protection,” with clients in particular from Greece and Cyprus needing a Jersey structure around assets to calm their nerves.

“Families are also getting more concerned about divorce. If you have four children, the chances are one of them will get divorced. So rich families feel under attack and want a stable base.”

Hedge fund managers including Blue Crest and Brevan Howard are also setting up on Jersey, which is beginning to rival Switzerland as a base for alternative investments, specifically being encouraged to the island by tax breaks established by the Locate Jersey initiative.

“Wealthy people here can blend into the background, with anonymity and no profile,” suggests Bedell’s Mr Slack, “No-one bats an eyelid if you live in a £10m ($14m) house. In a small village in England, you would have a lot more profile, and letters every time they want to raise money.”

Law firms are clearly keen to service the new players, providing them with estate planning and family office services.

“We are well placed to get involved in this. It’s the sort of business everyone on the island wants to see and more could join the hedge fund managers once people see friends and rivals come to his jurisdiction,” says Mr Mieklejohn, emphasising that Jersey can provide qualified staff for this type of “light footprint” business.

The Jersey authorities are also keen to expand the number of jurisdictions which use Jersey structures as a conduit for financial flows, particularly facilitating the investment of US and Asian alternative investment funds in Europe.

“In terms of asset management, plain vanilla bonds and equities for the retail market have long since vanished from Jersey,” says Carey Olsen’s Mr Mulholland. “Now it’s institutional money in private equity, real estate and hedge funds, plus ‘bums on seats’ in Jersey for hedge fund manager location.”

Among the deals he has structured was the £1bn IPO of Kennedy Wilson’s European real estate fund in 2014, followed by advising its £350m secondary equity issuance.

This industry employs 5,000 professionals, working for law firms and asset servicing companies including State Street, JP Morgan, Aztec, Saltgate, Crestbridge and Jersey Trust Company, administering £230bn worth of assets.

In addition to this healthy funds-listing business, allowing promoters to opt in or out of the European AIFMD rules, depending on where they want to market their investments, Carey Olsen is hoping that private banking will make a welcome return to the island.

“We did see some of the banks start to move their private banking centres away, but now they are bringing them back,” says Mr Mulholland. with those UK banks in the throes of restructuring their business keen to add wealth management capacity on the island.

The States of Jersey, the islands’ government, has been concerned at falling banking deposits. “Banking is the most profitable area for the States, so they are encouraging people to set up operations on the island,” says Baker & Partners’ Mr Shorrock.

The success of the island, historically, has been down to its ability to react quickly to market needs. “Jersey has an ability to re-invent itself and go in different directions,” says Cannacord’s Mr Cuming. “It is able to move on and adapt to changing needs of the global wealthy.”