Dublin endeavours to resuscitate Celtic tiger

Willie Slattery, State Street

A concerted effort to bring in international business and revive the Irish economy is underway, but how the fund industry responds to new regulations is key.

Willie Slattery, the larger-than-life Irish born and bred head of State Street’s offshore fund servicing business in Europe, surveys Dublin Docks from the rooftop of the American bank’s riverside building as if the city is his personal empire.

In fact, there was a time when it almost was. As head of financial regulation at the Central Bank of Ireland during the late 1980s and through the 1990s, he was one of the founding fathers of the International Financial Services Centre (IFSC), as it spread along the banks of the Liffey, through the forlorn capital’s dilapidated Docklands and confounded critics who scorned the very dream of a Celtic economic miracle.

But the miracle has now been and gone, although Mr Slattery recently accepted the opportunity to act as the financial services ‘Czar’ as chairman of the IFSC Ireland council and continues to sing the praises of his beloved financial centre in forceful terms, to anyone who will listen.

With dramatic gestures to the newly refurbished Aviva-sponsored Lansdowne Road football stadium and to what he calls the “dramatic escalation of the proliferation of the port area”, Mr Slattery’s practised tour-guide routine is stopped in its tracks by one particular sight – the skeleton of the half-built Anglo Irish Bank headquarters on the river’s opposite bank. At the height of the crisis in December 2008, the Irish government was forced to take a 75 per cent stake in the bank for €1.5bn, its shares plunged 98 per cent from their peak and trading was suspended on both Dublin and London stock exchanges.

Commissioned from the same builder who constructed the State Street offices, the 300,000 square foot concrete floors are surrounded by a real-life Meccano set. It stands as an admonishing monument, wagging an imaginary finger at the speculative property boom which eventually consumed the brief but glorious ‘Celtic Tiger’ interlude of Ireland’s bleak economic history.

But the State Street boss is convinced construction will soon recommence across the river, after local red tape has been dealt with. He talks about expanding projects being undertaken on behalf of employers including Facebook, which has set up its European HQ opposite his building and is expanding and recruiting rapidly in Dublin. Meanwhile, new age fellow travellers Google are also increasing their presence.

“There is no other major empty office block here in Dublin,” shouts Mr Slattery, in the face of a strong spring Irish breeze, almost daring visitors to disagree. “Not like the City of London.”

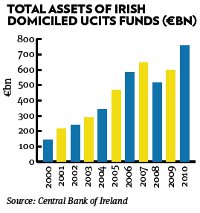

And the story he tells is not just one of tax-led financial services, but one of an outward-looking financial services hub, employing 11,000 people, expanding as part of a broader, internationally diversified economy. Latest figures from the Central Bank and Irish Funds Industry Association (IFIA) show total assets administered for more than 850 fund manufacturers have reached €1,880bn, up from €1,440bn a year ago.

But the very fact that Mr Slattery must defend his territory with such passion and attack any critics even before criticism is voiced, hints at reasons for this rear-guard action, with fund houses keen to look at Luxembourg and even Malta for domiciling new product launches. While Dublin accounts for 30 per cent of money market funds domiciled in Europe and 32 per cent of the growing exchange traded funds (ETF) market, it still lags behind Luxembourg’s continental-dominated industry. Funds with a Dublin domicile account for €965bn in assets, less than half the Luxembourg total.

Because Ireland endured such a tough history, in terms of famine, poverty and battles for political independence, when the good news of the financial services-led economy first emerged during the 1980s, there was an unwritten law that everybody must stick together and speak only well of the industry.

Today, there is more introspection, as the sector has matured, but a new concerted effort to help international business lift the moribund economy is firmly on the agenda.

Singing from the same sheet as Mr Slattery, in slightly gentler tones, is Kieran Fox, head of business development at the IFIA, currently preoccupied by the effects of the European regulatory onslaught, including amongst other rules, the consumer-led Ucits IV and the Alternative Investment Managers Directive (AIFMD), on his existing and potential membership.

How the IFIA responds to these regulations and helps redomicile Caribbean-based products, to give hedge fund managers access to a broader, European investing public, will be crucial to Ireland’s future as an international hub for investment funds’ expertise. Yet the speed with which the regulatory framework has been reconstructed has clearly taken many Dublin-based practitioners by surprise.

Changing plans

Mr Fox recalls how an Irish delegation visiting Brussels in January 2009 to address the issue of whether hedge funds should be regulated had to think on its feet.

“Everyone got there to discuss our feedback to the EU’s consultation paper,” remembers Mr Fox. “On the first morning, someone in the Commission stood up and said: ‘There has been a change of plan. We are no longer going to talk about responses to whether hedge funds should be regulated.’”

Instead, the Commission decided to present its plans to regulate alternative investments and proceeded to describe what these fledgling regulations should look like. “That certainly caught us all on the hop,” smiles Mr Fox, referring to “a collective sharp intake of breath around the room.”

But he does not deny the political reasons for the Franco-German pact which led to the Directive being fashioned from the fallout to the 2008 crisis and believes Dublin can prosper, even, realistically, as an overflow centre from Cayman-administered investment funds business. The island nation is currently some way behind in third place for hedge fund registrations behind Cayman and the US State of Delaware.

“If a manager or investors wanted a European-domiciled hedge fund, I think the overwhelmingly obvious place to have that is Ireland,” believes Mr Fox, particularly as long-standing Irish-regulated Qualifying Investor Funds, assets of which grew 35 per cent to €153bn during 2010, already take on board key considerations of the draft AIFMD regulations for managing and marketing hedge funds in Europe.

With European institutions and private clients eventually expected to increase allocations to non-traditional investments, the IFIA expects to become a natural home for the US funds which will seek to accommodate them. “A lot of the infrastructure and requirements of the AIFMD are already in place in Ireland. We service 43 per cent of the world’s hedge funds assets, so we have experience of the strategies and investments, as well as lawyers and a Central Bank which understands them. We already have a reputation for doing it.”

Harmonised brand

Central to Mr Fox’s plans to boost the standing of Dublin’s financial centre is to enhance the reputation of products regulated under this “accidental directive” to the level of respect currently witnessed for the Ucits generation, which underpinned the growth of the IFSC.

“To date, there is no harmonised alternative product in Europe, in the same way as there is a harmonised European retail brand,” says Mr Fox, warming to his theme.

“One of the successes of Ucits in recent years has been the ability of the products to be sold and distributed globally, including in Asia. Asian regulators and distributors like it, they understand that this is a harmonised regulation across 27 member states,” he says.

“The same thing could happen on the alternatives side. What could happen some years down the track is the AIFMD brand establishing itself as a harmonised, European-regulated hedge fund product. If institutions are looking to invest in or manage a hedge fund product globally, this might become the default brand of choice. If an Australian insurance company, for instance, is looking to invest in a hedge fund for its clients, they might prefer it is AIFMD-badged. This could be a positive, unintended consequence of AIFMD.”