Wealth transfer: Looking after the next generation

Wealth managers have struggled with digital engagement but must raise their game if they are to meet the expectations of an upcoming youthful cohort of potential clients

The massive transfer of global wealth between generations expected to occur over coming decades represents a great opportunity for private banks to capture a huge base of assets, but also a major challenge. The question is, will they be able to engage, at an early stage, with the demanding, highly international and mobile new crop of wealthy individuals?

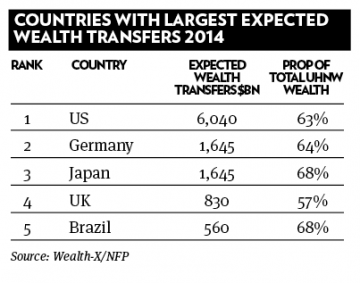

Within the next 30 years, the total value of global ultra high net worth wealth transferred down through generations is estimated to reach nearly $16tn (€15tn), the largest in history, according to a recent report from Wealth-X and New York-based insurance company NFP.

In order to capitalise on this inter-generational wealth shift, private banks need to develop a value proposition relevant to the next generation of inheritors, as well as retaining the loyalty and the assets of their clients.

Banks and consultants say younger clients have different attitudes towards investing: they expect transparency and control, they are not tied to traditional sources of investment advice or service and are largely digital natives.

“The next generation has grown up with the internet, their daily lives are influenced by Google, Amazon and Apple and they expect the same quality of digital experience with their wealth management firm as they do with other parts of their life,” says Bill Sullivan, global head of Market Intelligence at Capgemini Financial Services.

According to last year’s World Wealth Report, published by Capgemini and RBC Wealth Management, nearly 80 per cent of high net indviduals (HNWIs) under 40 are likely leave their wealth management firm due to a lack of integrated channel experience, ie being able to start a transaction via one channel and shift across different channels.

The wealth management industry has been a laggard when it comes to digital enablement, but this is changing, says Mr Sullivan. Banks need to provide best-in-class adviser enablement digital tools not only to meet the expectations of Next Gen HNWIs, but also to attract the best young talent.

However many institutions are restricted by legacy systems, processes and policies which makes this challenging to achieve. “Next Gen and millennials are the most educated, tech-savvy generation in the world and represent a natural opportunity for the wealth management industry, but meeting their expectations is an ongoing challenge for banks,” says Tim Tate, global head of Client Management at Citi Private Bank.

“While many are tethered to their smartphones and tablets, simply offering online and mobile banking services won’t be enough to build a long-lasting relationship.”

The global bank has created a digital engagement tool, ‘Citi Private Bank In View’ which is primarily designed for mobile devices. The platform, based on research with Next Gen clients, provides interactive information on portfolios, access to financial insights and education, and delivers transactional capabilities.

When combined with the bank’s regular educational Next Gen programmes run in London, New York and Singapore, it creates “a unique opportunity” for the children of UHNW clients to meet and learn together. The availability of the digital toolkit allows Next Gen clients to engage with each other in a secure environment before the event, and continue the social collaboration “virtually” once they return home.

“It is the ability to deliver this type of seamless digital and analogue experience that will define banks’ success with this segment in the coming years,” states Mr Tate.

Simply adding a digital layer to what is done today is not enough to become relevant to the next generation of clients, adds Stephen Wall, senior analyst at research and consultancy firm Aite Group. Wealth managers need to reassess their whole business model including fees, transparency, communication, performance, product and service suite.

“The decision to be digital and relevant to the next generation is all-embracing and must come from the top of a firm and be implemented all the way through a business. It is not just a small side project,” states Mr Wall.

The expectations of the old and new generations are aligned, when it comes to their desire for simplicity, honesty and fast access to advice, notes David Durlacher, head of relationship management at Swiss bank Julius Baer. “But those firms that are unwilling to invest in technology, demystify their terminology and capture the imagination of the next generation will find that they themselves will age and die,” says Mr Durlacher.

Firms unwilling to invest in technology, demystify terminology and capture the imagination of the next generation will age and die

Especially with the commoditisation of transactions and execution as a result of the rapid advancement of technology and growth of online trading platforms, “the increased threat of disintermediation translates to an urgent need for private banks to reduce their dependency on transaction revenue,” says Michael Benz, global head of private banking clients at Standard Chartered Bank. Banks need to increase their focus on “professionalising client relationships through specialist knowledge and customised advice”.

With bankers and advisers currently losing almost half of the assets under management during generational wealth transfer, according to the World Wealth Report 2014, a key aspect of succession planning is to introduce discussions about the future early on with the next generation, to engage them and understand specific needs, concerns and aspirations.

This thinking leads banks to offer seminars, workshops and courses, often in collaboration with educational institutions, designed to financially educate the next generation and develop leadership skills. For example, Standard Chartered, through its annual Wealth Masters Summer Education programme in Singapore, aims “at equipping young adults with the requisite tools and financial know-how to structure wealth plans and make the right investment decisions to meet their financial goals and objectives”.

But almost half of high net worth business owners in Asia, Africa and the Middle East do not have a formal wealth transfer plan in place, according to the bank’s research. In Asia, where wealth is largely in the hands of the first generation of entrepreneurs, Asian family businesses lose close to 60 per cent of their value at the point of transition. The big risk is that Asian economies, dominated by family-owned businesses, risk slowing their growth if the major clans fail to ensure successful transitions.

The next generation, typically better-educated and with more open perspectives, appreciates more the value of having succession planning conversations at an early stage, states Mr Benz. What is important is to respect subtleties, and cultural sensitivities especially in emerging markets, where businesses tend to be family-oriented and succession often a “taboo topic” to discuss.

Transmitting values

More than two thirds of the global ultra rich transferring their wealth are self-made individuals, according to the Wealth-X/NFP report, and wealth managers have a great chance to assist them to transmit their business ethos and values, and the proverb “shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations” from coming true.

At US private bankers Northern Trust, a team of people trained in family psychology, within the group’s Family Education and Governance practice, caters to help equip wealthy clients to pass on family values, also at the heart of the family’s success and financial wealth.

The two largest challenges facing owners of economic enterprises or closely held businesses are the transfer of so-called ‘trans-generational entrepreneurship’ and the nurturing of non-economic benefits of a family, says Northern Trust’s chief fiduciary officer Hugh Magill, citing a study from North West University professor of Family Enterprise John Ward.

“As wealth tends to disperse, it is important to inculcate in the next generation the importance of being entrepreneurial,” says Mr Magill.

This has to begin early in life, for example by equipping children to understand the value of money, of budgeting, of saving and eventually capital markets and investing, and finally their responsibility to be a productive member of the family.

Northern Trust can tailor a specific education curriculum for a client family, designed to educate their children about financial responsibility over a period of years, and then further down the line

discuss the family’s mission statement or constitution.

Implementing a robust, but flexible, governance framework offers business owners the best chance to pass on their family-held business to the next generations, notes Steve Faulkner, head of Private Business Advisory in JP Morgan’s Advice Lab, in New York. The global downturn has been a “wake-up call” for family businesses in this regard.

“Since the financial crisis, matriarchs and patriarchs of family businesses, globally, have a better appreciation of concentration risk, and so are taking steps to mitigate that risk,” says Mr Faulkner. “This does not necessarily mean selling the business,” although the proportion of family businesses that intend to do this has increased from 40 to 60 per cent, among JP Morgan clients.

“But it means thinking long and hard about what makes their business vulnerable to some of the risks they may have experienced in 2008 to 2009, and how they can better prepare so that they can be successful in passing it on to the next and future generations.”

Particularly if their intent is transferring the business to successive generations, business owners should follow some key rules, according to JP Morgan. These include creating a distribution policy, which identifies how much of the business wealth needs to be reinvested, and a liquidity pool invested in equities and alternatives in a complementary, non-correlated manner, which acts as counterweight to the business.

Deciding about allocation of control and establishing rules dealing with career advancement of both family members and key non-family members in the business are also crucial. Families may require that all family members gain a college degree and work for a number of years in another company before joining the family business.

“Fostering entrepreneurial vitality is one of the most difficult challenges family business owners face, as there is no textbook for how to do that,” says Mr Faulkner. As people learn more from their failures than from successes, clients should

create an environment for the future management team, where “they can fail in a constructive way so that is not debilitating to the business”.

Also, key to the survival of the family enterprise across generations is the creation of a mechanism allowing family members to exit the business, but making it not economically advantageous for them to do so.

The global financial crisis in many cases drove wealthy business owners, who saw the value of their business dramatically fall, to delay their planned wealth transfers. This means that today, in addition to those approaching retirement, there is a pent-up demand for wealth planning services for that generation hoping to transfer assets seven years ago, notes Richard Kollauf, estate planning manager at BMO Private Bank in Chicago. This offers banks able to adopt a holistic approach a “once in a lifetime” opportunity to become their clients’ trusted business and wealth adviser.

But even in North America, which is expected to be the source of the largest world’s transfer of UHNW wealth in the next 30 years, with $6,350bn changing hands according to Wealth-X, the majority of business owners do not have succession plans. This is also the key reason why wealth is not preserved across generations, followed by lack of education and “role-modelling” by the older generation for the next one, says Mr Kollauf.

“The business owner is so consumed by running their business, and just accumulating wealth and does not spend any time on the business, thinking about planning for passing it on,” he says.

By bringing to the table financial, estate, succession planning and other fiduciary services, a bank has the opportunity to deepen the client relationship and understand clients better, and be more holistic in its approach. This means being able to provide better advice, driving clients to rely on the bank more, potentially choosing it as their first service provider in case of a liquidity event, for example, explains Mr Kollauf.

In wealth management, offering a multi-generational view on family wealth, which looks at the needs and objectives of the current and future generations, is a vital approach, states Northern Trust’s Mr Magill.

A bank needs to offer not only private banking and portfolio management services, but also onshore and offshore fiduciary services, as well as advisory services, including family education and governance, tax and financial planning, and needs to be able to manage unique assets and provide asset servicing, particularly critical for portfolios of multinational families, he says.

Philanthropic planning is also increasingly important to meet people’s growing desire to give back to society. Wealthy parents worry they risk extinguishing their children’s productivity, which is important for self-worth. And the question they increasingly ask themselves today is, when it comes to the transfer of their assets, how much is enough and how much is too much, explains Mr Magill. Many wealthy believe that wealth “has to serve as a safety net but not as a hammock, it is not a place to rest, but for protection.”