Mediolanum’s multi-channel approach stands test of time

Massimo Doris, Mediolanum

The Italian firm believes younger cohorts of clients will come to appreciate its advice-led business model

When, back in 1982, entrepreneur Ennio Doris, the late founder and president of Banca Mediolanum, in partnership with media tycoon and controversial former Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi, created a network of financial advisers, Programma Italia – predecessor of Banca Mediolanum – he could not have predicted how resilient the bank’s business model would prove 40 years later, during a global pandemic.

A forerunner of digital banking, Banca Mediolanum launched in 1997, with no physical branches. Instead, it touted its wares by phone and teletext, pioneering what it called a ‘multi-channel’ approach to personal investment.

It strove to be “the bank built around you”, as its founder would say in the bank’s iconic TV slot, while drawing a circle with a stick on a dried-up salt lake.

“The bank is the result of my father’s great foresight, who was the first in Italy to offer clients financial advice at 360-degrees,” explains Massimo Doris, Ennio’s son and the CEO of Banca Mediolanum Group since 2015.

Today Banca Mediolanum is a bank, insurance and asset management conglomerate, relying on 5800 financial advisers, known as ‘family bankers’, serving more than 2.3m customers, mainly in the upper affluent segment, owning €90,000 ($920,000) in assets on average, in Italy and Spain.

Twenty-five years ago, the group established its asset management arm, Mediolanum International Funds, in Dublin, to take advantage of the Irish city’s expanding financial services ecosystem. Dublin’s flexible regulations allowed innovative products to be launched, with a short time to market, for cross-border distribution. This proved much more straightforward than dealing with Italian regulators.

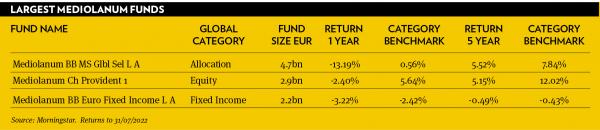

A pioneer of the sub-advisory model in Europe, today the asset management firm has €58bn in client assets. Their management is largely delegated to carefully selected third party large and boutique managers. The investment house then blends these funds into actively managed multi-manager and multi-asset solutions portfolios, claiming it can personalise them for individual clients.

Good times

Like his father before him, and the rest of the bank’s inner sanctum, Mr Doris Jnr is full of enthusiasm, even in the most difficult times. “Last year was our best year ever, in terms of financial results, and the best year before then was 2020,” says Mr Doris, speaking at the investment firm’s Dublin headquarters.

In 2021, the bank’s total assets, under management and administration, grew 16 per cent to €108bn. In the first five months of this year, the bank enjoyed €3.8bn of total net inflows, 70 per cent of which ended up in managed assets. These include popular, fiscally advantageous unit-linked insurance plans, as well as managed accounts.

Investments in digitalisation, made six to seven years ago, appear to have paid off. “We had to insist a lot that the sales networks moved from paper to digital contracts,” reports Mr Doris, but when the pandemic hit, advisers were used to working with the new system and digital contracts reached a peak of 97 per cent during the strict Italian lockdown.

Family bankers have now resumed face-to-face client meetings, but continue to use digital tools and video calls, allowing them to meet more customers each day and manage greater numbers of clients.

The tailored financial advice provided by our family bankers is the most critical added value for clients

Yet, Mr Doris credits the bank’s results largely to its advice-centred business model. “The tailored financial advice provided by our family bankers is the most critical added value for clients,” he says. “While product performance remains extremely important, customers tend to buy high and sell low, destroying the performance of the fund manager, on average.”

He also plays down the high level of fees which active multi-manager packages are known for, adding that unlike “cheap and cheerful” exchange traded funds, these solutions incorporate management, distribution and advisory costs.

“A big mistake people make is not comparing apples to apples, when it comes to fees,” he argues.

This notion of family bankers playing a key role in allocating assets is central to the Mediolanum model. Fifty-seven per cent of client assets at Banca Mediolanum are invested in equities, versus 20-30 per cent at competitors, claims Mr Doris. His clients’ historically relatively high exposure to equities has been further boosted by low interest rates, with close to 90 per cent of inflows going into equities over the past few years.

Even the typically conservative Italian bondholders are persuaded by advisers to enter the stockmarket gradually and gently, through automated switching from deposits and money markets, taking advantage of market drops. “Equity is the best asset class to invest into for the very long run, and in my opinion, most of people’s investments should go towards it,” he says, although the firm expects bigger allocations to fixed income to cover short and medium-term needs, as interest rates increase.

From sales to advice

Despite this success, the definitive model which Mediolanum has designed is constantly under external scrutiny. Critics label its use of tied agents, focused on selling funds to Italy’s mass affluent client base, intrusive and aggressive. There is also a question mark over whether this traditional “we know best” way of doing business can continue to stay relevant to younger cohorts of self-directed investors.

Mr Doris argues that the model is not static and has continued to evolve since his father’s heyday. The adviser has replaced the salesperson of the 1980s and 1990s, he says. While in the past, advisers made their living off product subscriptions or entry fees, driving them to use hard selling techniques and always find new clients, today one-off fees represent just 20 per cent of their total income.

Most of the advisers’ remuneration, around 60 to 70 per cent, comes from managing clients’ savings over the longer term, representing a cut of the annual fees clients pay on managed assets. An annual bonus from the bank is linked to net new money brought in by the adviser.

“Today’s financial advisers have become clients’ trade union reps,” jokes Mr Doris, adding that they will care for their clients until retirement, never attempting to offload inappropriate products. “Unlike bank employees, our advisers have no targets linked to specific products,” he says. This shift in business model, says Mr Doris, is evident from changing patterns of assets per family banker, increasing from €8.6m in 2011 to €23m today.

Advancements in technology have enabled advisers to create “risk efficient, balanced and diversified portfolios” and to monitor them, at scale, while clients check their investments on the banking app.

Mr Doris plays down the concept of “cold calling”, claiming it was little used in the past and even less so today. Instead, family bankers acquire new clients through referrals. While men still represent the lion’s share of advisers, he is confident that the increasing numbers of women with finance and economics degrees will become interested in the “certain flexibility” which the job allows.

He is keen to attract new staff from outside the financial world. Currently these recruits represent 70 per cent of advisers receiving intensive training in finance at Mediolanum Corporate University.

In addition, since last year, select graduates also spend a six month stint at the campus, and then begin to assist senior bankers with administrative tasks or management of smaller clients, allowing senior bankers to focus on more lucrative customers. New recruits receive a share of the senior banker’s commissions, with a minimum of €25,000 salary per year.

The world is more and more complex and people need financial advice

“Senior bankers are queuing up for a banker consultant to assist them,” he reveals. “So we had to accelerate the programme because we were overwhelmed with requests.” Mr Doris is confident the new initiative will help accelerate growth, in addition to opening job opportunities to graduates in a sector not previously accessible.

“When you are 24 years old, your friends do not have any money, and your friends’ parents will not trust you with their savings,’’ explains Mr Doris.

Lots to learn

Unlike many bank bosses, he is not too preoccupied about engaging new generations, believing widespread research findings about younger cohorts’ apparent disdain for financial advisers and banking services should be taken with a pinch of salt.

“The young do not have a clue about what they are saying, because they have no money and do not need to manage it. Theirs is just grapevine talk,” he says dismissively. Once they have worked hard to put savings aside, then “money tastes completely different”, especially when they get married, have a family, and need a mortgage or a loan.

Smart bankers, he says, try and engage clients’ children early on, knowing the relationship with them will evolve as they enter adulthood.

This bedrock of face-to-face financial advice will continue to evolve, despite recent trends to self-directed platforms and online trading, believes Mr Doris. In Italy, financial advisers’ networks’ market share in managing wealth has doubled to 17.5 per cent over the past 10 years, while that of traditional banks has reduced by 10 percentage points to 62 per cent, according to consulting firm Prometeia.

“The world is more and more complex and people need financial advice,” he says, but financial advisory must be supported by “excellent” digital services.

“I am sure some individuals of the next generation will want to use digital platforms only and not speak to advisers, but many will learn the hard way, lose their money and be grateful that someone is there to help them. I bet Banca Mediolanum on this.”