AIFMD opens hedge fund universe to wider audience

Timothy Bell, UBS Wealth Management

AIFMD should entice a large number of new investors into hedge funds, but will the high entry costs of complying with the new directive mean only larger fund providers will be able to offer these new vehicles?

So-called Newcits, that is hedge funds wrapped in the Ucits format, have grown substantially since they were launched in the mid 2000s in Europe. They catered for investors unable to invest in offshore, unregulated vehicles. But the AIFMD (Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive), which came into force in July last year, is expected to be a catalyst for new hedge fund investors.

While Ucits alternatives have to abide by rules and constraints which traditional offshore hedge funds are not subject to, for example those relating to concentration rules, eligible assets and minimum liquidity, AIFMD-compliant managers will be able to deploy exactly the same strategy followed by the main offshore fund in a regulated onshore fund in Europe, explains Nathanael Benzaken, deputy head of alternative investments at Lyxor.

“The AIFMD is bringing onshore what used to be offshore,” he says. “What is new is the infrastructure set-up and the more robust guidelines for the fund manager.”

Fund managers are asked to comply with a number of rules, which were previously merely considered to just be best practice. These include appointing a permanent risk manager and an independent custodian, and adhere to more strict reporting requirements and the new remuneration policy on bonuses, which will have to be reinvested in the fund.

Investors unable to invest in offshore funds, and who have so far seen Ucits alternative funds as their only available option, will gain access to strategies that are not eligible for the Ucits format, says Mr Benzaken. These include those where the underlying is too illiquid or the requirement to leverage is too high.

“This new client segment is unexplored, and very sizeable,” he says, citing small to mid-sized institutional investors, insurance companies, sophisticated private banking clients and large family offices.

Many strategies have characteristics that make them intrinsically Ucits-compliant and managers may decide to offer an AIFMD-compliant fund, more leveraged, concentrated and illiquid, as well as a Ucits version.

But whereas Ucits funds have been designed and conceived for the European market, although they have had some international success, particularly in Asia, AIFMD-compliant funds are the only onshore solution that can compete worldwide, according to Mr Benzaken.

“With AIFMD, for once in Europe we have the opportunity to pioneer a new international, global solution, which comes with a more robust infrastructure than offshore solutions.”

However, being compliant with the new regulation requires a very robust infrastructure and a significant team, and the entry costs for a manager are higher compared to running an offshore fund. “This will definitely put pressure on the smaller fund management firms,” believes Mr Benzaken.

The institutionalisation of the hedge fund industry, further driven by regulation, will attract new clients. Institutions such as private banks will have a much broader universe of hedge funds to access and will be able to give clients added value, according to Lyxor.

But in order to be able sell AIFMD-compliant funds, under Mifid (Markets in Financial Instruments Directive) regulation, private banks will need to convert some of their sophisticated clients into professional investors – and this requires a lot more paperwork and a higher net worth.

Plus points

However, one of the developments that has come to light recently is that funds can also be AIFMD ‘plus’, meaning they can be marketed to more retail clients. It is still not certain whether AIFMD ‘plus’ funds will have the same characteristics as Ucits alternatives, while unclear regulations do not help fund allocators raise money, explains Marc de Kloe, head of alternatives and funds at ABN Amro Private Banking.

While the Dutch Bank is currently focusing on Ucits alternatives and on AIFMD ‘plus’ funds, it expects to evolve to AIFMD-compliant funds in the future, particularly in order to distribute more illiquid strategies. This will involve signing up some of their clients as professionals. “But it is an evolution, it will take time,” says Mr De Kloe.

Other major private banks, such as UBS, are today entirely focused on Ucits alternatives. The global bank declined to comment on how AIFMD could affect their hedge fund offering and their client classification at this stage.

“Our focus is on Ucits when it comes to hedge funds,” says Timothy Bell, global head of hedge funds advisory at UBS Wealth Management. “Investors prefer Ucits alternatives not because they are shying away from illiquidity but because they have become more polarised in terms of how they wish to invest, when it comes to hedge funds, preferring the private equity model for illiquid investments with its predefined lock-up period.”

Pascal Botteron, global head of Global Client Group Alternative Investments at Deutsche Bank, notes that while five years ago alternative Ucits were predominantly used by private banks, today it is more of an industry investment vehicle, with insurance companies, asset managers and multi-asset managers also investing in these regulated funds.

Increased regulatory costs are going to favour big institutions, says Mr Botteron, as the fixed cost of seeking legal advice, providing reporting, fund registration and generally complying to regulation is increasing for all alternatives. Fund platforms are growing, he says, as they offer advantages of better security, cash control, and scale. Smaller fund firms, in particular, are expected to outsource ever more of their reporting, depositary and compliance requirements to the platforms going forward.

Ready to go?

• With only six months to go until full implementation of the AIFMD, fewer than 20 per cent of alternative investment fund managers have submitted an application to their regulator for AIFMD authorisation, according to recent research by BNY Mellon

• The mean cost of AIFMD compliance is expected to be $300,000 (€220,000), while the majority of survey respondents believe the costs of fulfilling requirements will be at least $100,000 – and potentially over $250,000 – per institution.

• 88 per cent of participants believed the costs of funds would increase as a result of AIFMD

“AIFMD will reinvigorate the investment boutiques,” believes Jerome Lussan, founder of hedge fund consultancy firm Laven Partners. The AIFMD stamp, like the Ucits one, will help their distribution, and this may in part reverse the current trend where inflows are going predominantly to big hedge fund houses.

The cost of complying with regulation in Europe is not very high for boutiques, sustains Mr Lussan, if they are smart enough and shop around for service provider options.

Even those boutique investment firms that are small enough to be partly exempted by AIFMD will want to comply with regulatory requirements, agrees ABN Amro’s Mr de Kloe, because they will increasingly see it as a stamp of approval, which will help draw investors’ money.

In general, though, sizeable investors or large private banking groups, such as ABN Amro, only invest in funds having a critical mass. “If we want to be able to invest into these more start up hedge funds, particularly the newer Ucits funds, we will need to change some of our requirements, make them a bit more flexible, not in terms of the quality of the manager, but certainly in terms of the physical constraints or AUM,” states Mr de Kloe.

A fund with $5-$10bn (€3.7-€7.4bn) or more in assets gives comfort to investors, because of the element of stability it affords and the larger infrastructure associated with it, says Ken Heinz, president of Hedge Fund Research (HFR), but not always because the performance is higher.

What really limits the growth of the small funds is the constraint that investors have on what percentage of the total capital of a fund they are willing or allowed to be.

Also, with the increasingly smaller influence of the fund of funds, which historically have taken that risk on small funds, very few are willing to be seed investors or early stage investors, he says, with most only happy to invest in a fund when it has reached $100m or $200m in assets.

“What you need in order for the small and mid-sized funds to have an easier time growing is a normalisation of investor risk tolerance, as investors will be more willing to take the risk associated with a fund that generates a higher performance,” he says.

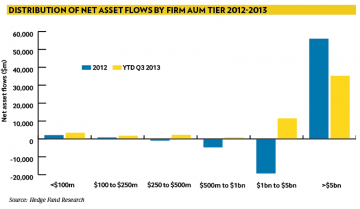

Investors’ moods seem to be changing already. According to HFR, while a couple of years ago outflows hit funds with less than $500m, in favour of funds with $500m/$1bn and higher, last year trend flows have been slightly swinging back the other way, although larger funds continued to prove popular.

Where small and mid-sized funds have been able to compete with larger funds is on fees. “Fees are one area where the small and mid-sized funds have the ability to compete with the well established ones, and I think they need to,” says Mr Heinz.

Last year, there was a continued decline in both management and incentive fees, with more and more funds asking for 1-1.5 per cent and 17 to 10 per cent, leading to lower numbers across the board.

Again, it is all a question of risk tolerance. The more risk-averse choice for investors is to put money into the well established fund which charges 2 and 20, but they can expect to pay lower fees as part of taking some risk associated with investing outside that core base of well known funds. In some cases, for very small funds, seed investors can become not only limited partners but also equity holders.

Brand name, large single hedge fund strategies, have grown significantly over the recent few years, probably to the limit of their capacity, says Arie Assayag, head of UBP Alternative Investments. But the interest is now on a new generation of managers. “In our customised, advisory mandates or what we call ‘directional’ absolute return strategies, we are investing in brand names, but our focus and value proposition has been really to identify second generation managers with high potential and very focussed on performance,” he says.

These are typically mono-strategy funds – managing between €500 and €2bn in assets, and are used in managed accounts for the bank’s absolute return programme. To generate an absolute return in a liquid format, with typically monthly liquidity – managers need to master trading skills, as opposed to arbitrage skills. And cost of trading would be too high for large funds, says Mr Assayag. These new generation managers are also “open minded to reduce their fees constructively”.

“If we use these managers for our managed accounts, we have a clear objective and scale, which help us bring down fees,” he explains. “That means we can reduce our overall expense ratio and we can attract some of the clients that are constrained with regards to fees.”

Non-directional absolute return strategies will grow very fast, expects Mr Assayag, to meet the appetite of more conservative clients for strategies de-correlated from other asset classes.

Impact of regulation

While Ucits regulation has been tried and tested, procedures for selling alternative funds under AIFMD are still vague and vary across Europe. In France and Spain, for example, there is currently no regime allowing foreign fund managers to sell an alternative fund, other than reverse solicitation.

Italy and Belgium have not yet implemented AIFMD, and fund managers either have to rely on Ucits funds or in some cases on reverse solicitation.

The deadline for alternative managers to register for AIFMD, initially set in July 2013, has been extended to July 2014, with the view that from 2018 AIFMs will be able to passport their fund in the European Union. In the meantime, in order to be able to promote their products, alternative managers have to register them in the country where they want to distribute, or at least notify the local regulator in jurisdictions traditionally more welcoming to alternative investments.

But lack of regulatory clarity has led many hedge fund managers, in particular US-based ones, to suspend the marketing of a lot of their products, as each country today has different rules about selling alternatives.

“There are a few legitimate reasons why alternative managers may not hurry to register their fund,” says Laven Partners’ Jerome Lussan. “But in relation to the UK people should hurry, because legislation is pretty clear.”

There is no doubt that regulation such as AIFMD and, more recently, the Volcker rule in the US, resulting in banks having to wind down their proprietary trading activities, will continue to have an impact on the growth of the hedge fund industry. But the misconception is that it may hinder it, says HFR’s Ken Heinz. He estimates that over the next three to five years the industry will continue to grow, doubling its assets under management to $5tn (€3.7tn).

Regulation can accelerate the expansion of the industry, as investors are more comfortable with the higher transparency it offers, he says. Also, the reduction of proprietary trading in US and, to an extent, European financial institutions, will lead to a clearer split between depositary capital and risk capital, and the hedge fund industry will attract investors that had historically looked at investing in bank stocks because of the earnings result of their proprietary trading activities.

Looking forward, the influence of Asian investors is expected to grow and more hedge funds will be located in that region, investing across Asia. Today it is a very US and European-centric industry, but in the future it will be more balanced across those three regions, predicts Mr Heinz.