Learning to live with heightened political risk

Brexit, the US election and the rise of populism are just some of the geopolitical risks stalking global markets. How significant are these threats, and how should private portfolios be positioned in response?

Like it or not, political and economic nationalism are once again becoming forces to be reckoned with on the world stage.

Following the British public’s narrow vote to leave the European Union, the period of post-war growth and stability which the Continent has enjoyed is under serious threat. Right wing populist parties, never known for policies of inclusion and cohesion or economic expertise, have been gaining popularity in the UK, France, Austria, Hungary and Poland.

The political picture elsewhere is similarly concerning. The emerging powers of China, Russia and Turkey all have traditional, uncompromising strongmen at their helms, presiding over increasingly authoritarian state machinery and unafraid to flex their military muscles across their home regions and beyond.

All of these developments are heralding a heightened state of geopolitical tension and risk, which affects not only inter-linked economies, but also the stock and bond markets which determine the value of private portfolios. Moreover, the situation is not a stable one of long-term military stand-offs which predominated during the Cold War.

Investors have to constantly re-assess the geopolitical risks they face, says Leo Grohowski, chief investment officer of BNY Mellon Wealth Management in New York. “What investors fear most depends almost on which week you ask,” says Mr Grohowski, whose investment teams battle to take into account the ever-changing sources of mayhem abruptly gushing out across the world. In mid-July, for instance, his fear table was topped by the fallout of the failed coup d’etat in Turkey, once a darling of emerging market investors.

Major drivers of the recent increase in populism

Long period of sluggish economic growth

Increase in income inequality, including a decline in middle-class incomes

Rise in immigration and increase in cultural and religious diversity

Populist movements have appeal when the economic pie is not growing, it is being divided unevenly and there is a perception that outsiders are competing unfairly for what remains

Source: MSCI, Goodwin Matthew 2011, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung and Social Europe 2015

However, some of the biggest risks are “ongoing”, he says, citing Russia, Isis and the highly uncertain outcome of the forthcoming US election. In the week that Mr Grohowski spoke to PWM, Russia’s relations with the West took another turn for the worse after its track and field athletes were banned from the Rio Summer Olympics following revelations of mass doping; Isis was linked to a terror attack in Germany; and Donald Trump, the unpredictable Republican US presidential candidate, blew holes into the security blanket protecting developed markets from Russian aggression, by suggesting the US would not necessarily come to the aid of all Nato members.

“This is one of the most elevated periods of geopolitical risk that I’ve ever had to think about in my 35 years as a professional investor,” says Mr Grohowski. “It’s going to make for a more volatile period in markets for years ahead.”

The sense of geopolitical risk magnified massively late in the European night of Thursday 23 June, when it became apparent the UK had voted to leave the EU in that day’s referendum. Stockmarkets fell abruptly around the world on fears of a political and economic fragmentation of Europe, though many rapidly regained lost ground.

“Political risks have always been there, but have seemed more hypothetical than real,” says Amin Rajan, CEO of UK-based thinktank Create-Research. “Now that has changed.”

He cites several “moderate likelihood/high impact risks lurking in the background”, including “turmoil in the EU”, a “hard landing” in China, “currency wars”, and the election of Mr Trump. “Any one of them has the capacity to cause big market turmoil,” says Mr Rajan – but “the key risk” is the “the fallout from Brexit, which is potentially devastating for the EU”.

In response to all these fears, private clients are “significantly overweight in cash” – though he says this also reflects inflated prices caused by quantitative easing. Where they do invest in equities, wealthy families favour those with high dividends, high free cash flow and strong pricing power, says Mr Rajan.

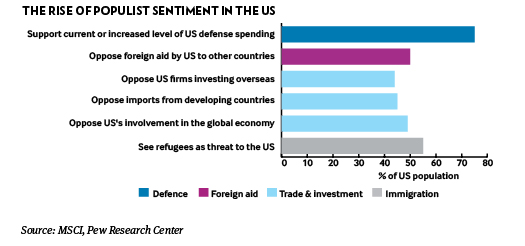

PREVALENCE OF POPULISM

Brexit has implications outside Europe too: it suggests that populism – where politicians devise policies based on what people want, rather than what elites think is best – is on the rise. The rise of populism is the political risk most cited by wealth managers. Most of Britain’s business, political and academic elite wanted to remain in the EU; in the US Mr Trump has raised doubts about policies scarcely questioned by the Washington establishment for decades. He has also won the support of many working-class Americans by calling for more protectionism.

“Populism tends to drive protectionism,” claims Cesar Perez Ruiz, chief investment officer at Pictet Wealth Management in Geneva. “That is what has happened in the UK,” he says, suggesting the vote for Brexit as a form of protectionism. Brexit voters’ objection to the free movement of people from mainland Europe to the UK has similar origins and effects to the objection of people in other countries to free trade, he believes. Mr Perez Ruiz sees a long-term cause behind this populism – and hence a long-term effect on markets.

“We are in a more polarised world, with greater income inequality, which has led to the rise of populism,” he says. “Because of this populism, volatility will be greater,” says Mr Perez Ruiz, predicting more such shock political events ahead. Portfolio managers must be prepared for further equivalents to the Brexit vote. “You need to trade that volatility to your clients’ benefit, using volatility as an asset class,” he suggests.

Pictet had already employed this strategy in the run-up to the Brexit referendum, buying put options on the FTSE 250, Nikkei 225, S&P 500 and Stoxx Europe 600 equity indices, all of which fell sharply after the vote. “We were ready to pay premiums to protect clients because it was very cheap to do so,” says Mr Perez Ruiz. “That protection really worked, and we took profits on half the position.”

In common with some other wealth managers, Pictet has chosen protection rather than flight, a more positive trend than the private banking norm identified by Mr Rajan at Create-Research.

“Despite the volatility we still feel the trend is up,” says Mr Perez Ruiz. “Brexit wasn’t able to derail the global economy.” Pictet is, in particular, bullish about US equities, in which it is overweight because of the positive dynamics of the US economy: “If we are able to jump all the hurdles we see – many of them political – it is very possible we will end up with double-digit equity returns,” explains Mr Perez Ruiz.

Trump in the White House?

Many are also far from despondent about Mr Trump, while acknowledging the uncertainty he creates. “In French we say ‘L’habit ne fait pas le moine’, ” notes Frédéric Lamotte, global head of market and investment solutions at Indosuez Wealth Management in Geneva: clothes do not make the monk. “But I believe that if you wear the clothes of the monk you become like a monk. In the same way, if Trump becomes president he will behave like a president,” moderating his tone on entering office.

In common with Pictet, Indosuez also downplays the effect of Brexit on Europe. “There may be a positive from Brexit,” says Mr Lamotte. “I was fearing at one point that Italy was going to be the weaker link, but maybe Brexit is helping Italy to stay in the EU.”

If Trump becomes president he will behave like a president

He notes the shock among young people in Britain, who overwhelmingly wanted to stay in the EU, on realising their low turnout had contributed to the referendum result. Mr Lamotte speculates that should the Italian people also be given the chance to decide on whether to remain, its youth will not make the same mistake. Indosuez is overweight European equities.

Pau Morilla-Giner, chief investment officer at London & Capital in London, thinks a Trump victory will actually boost US stocks by accelerating economic growth. “Trump will certainly increase infrastructure spending if he becomes president, and this public spending will have an impact on growth,” he says. Mr Morilla-Giner estimates this could contribute 0.5 to 1 percent to US GDP – boosting growth in 2017 to 2.5 to 3 per cent. He acknowledges long-term risks posed by a Trump Presidency, including the possibility he may increase protectionism; in late July the Republican candidate threatened to withdraw the US from the World Trade Organisation, which regulates international trade. However, Mr Morilla-Giner notes that even if this hits US exports, they account for a relatively small share of US GDP: 12.6 percent last year.

The dollar assets of L&C’s private clients will also benefit, he says, from global uncertainty. “Every time we have a hiccup, whether over Russia, the banks, or the fall in commodity prices, everyone will gravitate to safety; the dollar is still a major beneficiary of that.”

There is, therefore, a fair degree of optimism about risk assets in selected markets, amid all the fear. Wealth managers are distinguishing carefully between uncertainty and downright pessimism.

Nevertheless, uncertainty is a powerful force in financial markets – and is all the stronger because of the journey that markets have made, says BNY Mellon’s Mr Grohowski. “One reason why volatility will be higher is because market prices are much more fairly valued”, he explains. “Markets are able to withstand more bad news when they’re inexpensively priced. But markets have come a long way since the financial crisis.”

He notes, in particular, the rise in the S&P 500, from a trough of 666 in 2009 to above 2,100 in late July 2016. Having enjoyed good returns in many risk assets for some time, “investors might be wondering if they’ve overstayed their welcome”.

Geopolitical risk breeds uncertainty all the more powerfully because it is “unquantifiable”, he notes. For example, even if a wealth manager had predicted Brexit – and most admit to PWM that they expected a Remain vote – it would have been hard for them to come up with a cogent view of a fitting level for the heavily-domestically focused FTSE 250.

BNY Mellon’s solution has been to “ramp up exposure to alternatives – which we call ‘diversifiers’,” says Mr Grohowski. “They might not provide the double-digit returns that investors enjoyed in 2008-15, but investors are going to enjoy a smoother ride.” For a “truly balanced portfolio”, with 20 to 30 per cent exposure to alternatives such as long-short strategies and private equity, Mr Grohowski thinks investors can hope for 5 to 7 per cent returns.

However, the firm remains “amply exposed” to global equities in its model portfolios, with an overweight position in the US, though with a neutral stance in other developed markets and an underweight in emerging markets. These are often shunned in uncertain times because of their volatile tendencies.

Opportunities in Asia

ABN Amro Private Bank is also reasonably exposed to risk assets, with a neutral position in equities.

“We don’t like the uncertainty, but it’s not the end of the world for investors,” says Didier Duret, chief investment officer in Amsterdam.

For example, he sees opportunities in Asian emerging market equities such as China, Korea and Taiwan, because the flight to yen safety after the Brexit vote has made their exports more competitive, although by late July this had somewhat dissipated.

At the same time, Mr Duret downplays China’s territorial disputes over various islands and waters on the grounds that “there is nothing new – this has always been the case”.

“Brexit is simply one element of the return of politics to the scene – the UK is very much in the vanguard, as always,” notes Mr Duret, with a certain mischievousness. However, “it doesn’t mean the end game is fragmentation”, he says, echoing the views of other wealth managers that the EU will remain intact aside from the UK’s departure. Instead, “the end of the game is fiscal stimulus, which will be good for demand”.

He notes the announcement after the Brexit vote by George Osborne, in one of his last acts as the UK finance minister, that the country would cut corporation tax to show that the UK still, as Mr Osborne put it, “open for business”.

On the issue of fiscal policy, at least, many wealth managers agree with populist politicians – coming into line with received opinion among economists, which has gradually turned against austerity. Wealth managers may, in other respects, learn to not to worry about populism so much – even if they can never quite bring themselves to love it.

Navigating the Brexit fallout

While London’s wealth managers may have a sense of economic gloom about the UK economy in the wake of the Brexit referendum result, this does not stop them from seeing plenty of opportunities in UK markets.

The base case scenarios from London & Capital is that UK GDP growth will stall at zero next year. Pau Morilla-Giner, chief investment officer, notes the fall in business investment even before the result, and predicts that it could slide further – shaving as much as 2 per cent from GDP. He also believes the post-Brexit drop in job vacancies and house prices will hit consumer confidence.

This gloom is shared to a lesser degree by Swiss bank Pictet, which has halved its forecast for UK growth next year to 0.9 percent for similar reasons. But even L&C, whose view of the economy is at the gloomier end of the wealth manager spectrum, sees opportunities in the UK.

“We don’t have investments in any stocks that generate more than half of their revenue in sterling,” says Mr Morilla-Giner, who believes profits of domestically-focused companies will suffer. However, L&C thinks export-heavy companies, such as Rolls-Royce, will be “net beneficiaries” of Brexit, because of “prolonged” sterling weakness.

Pictet has responded to Brexit by investing in the FTSE 100, but with a partial currency hedge. Chief investment officer Cesar Perez Ruiz cites the opportunities for foreign companies to acquire UK companies more cheaply because of the currency’s fall, with acquisition prices still offering large stock price gains to investors. They did not have to wait long: less than a month after the vote, SoftBank, the Japanese telecoms group, announced an agreement to buy ARM, the UK chip designer.

But Chris Hills, London-based chief investment officer at Investec Wealth & Investment, whose clients are predominantly sterling-denominated, says the most immediate post-Brexit opportunities have been domestically-focused mid-caps, such as housebuilders and brewers, which the wealth manager started buying one week after the vote. He thinks their profit outlook has been hit by the result, but not enough to justify the deep slump in stock prices in the days afterwards.

In the longer term, Mr Hills sees opportunities in FTSE 100 companies with substantial dollar revenue, given his view that sterling may well fall further below its mid-July level of $1.31.